According to Kew, only three percent of current published discoveries are being made by woman botanists. It’s important to acknowledge implications such as this gender gap, because authorities can shape how we as students perceive and engage with science. Our research highlights western science’s legacies of dispossession, colonialism and imperialism, which brings to question the accessibility of scientific discovery as well as who is not being credited.

Please introduce yourself.

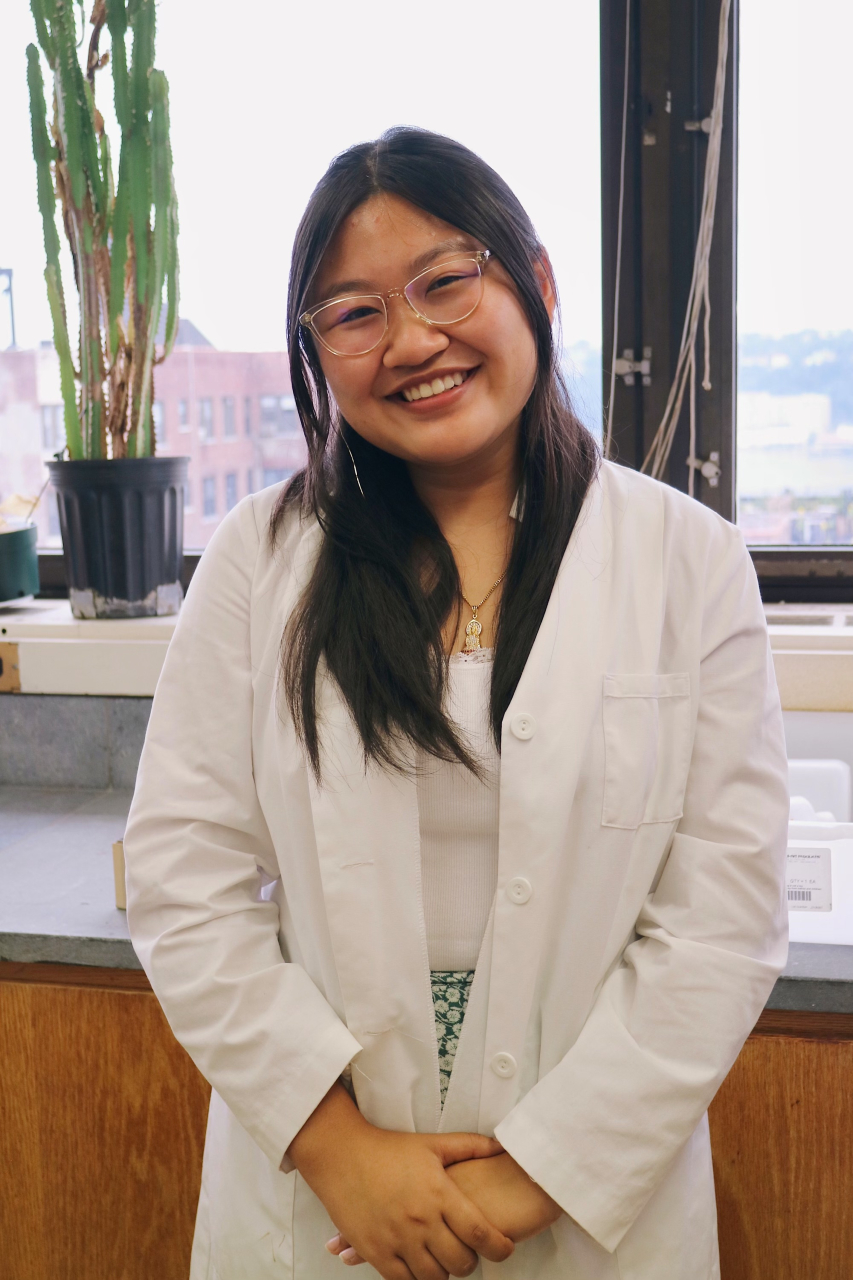

My name is Tiffany Vo, I’m a third year Barnard student majoring in medical anthropology. I was born and raised in Portland, Oregon. It was through the Multnomah County Education Service District’s Outdoor School Program that I was first introduced to plant field studies and developed an interest in the life sciences. In my free time, I enjoy photographing on film, cooking, and curating playlists.

This summer, you conducted research under the mentorship of Professor Hilary Callahan. Could you please describe your project? What are some of the methodologies you used and what are the goals of the project?

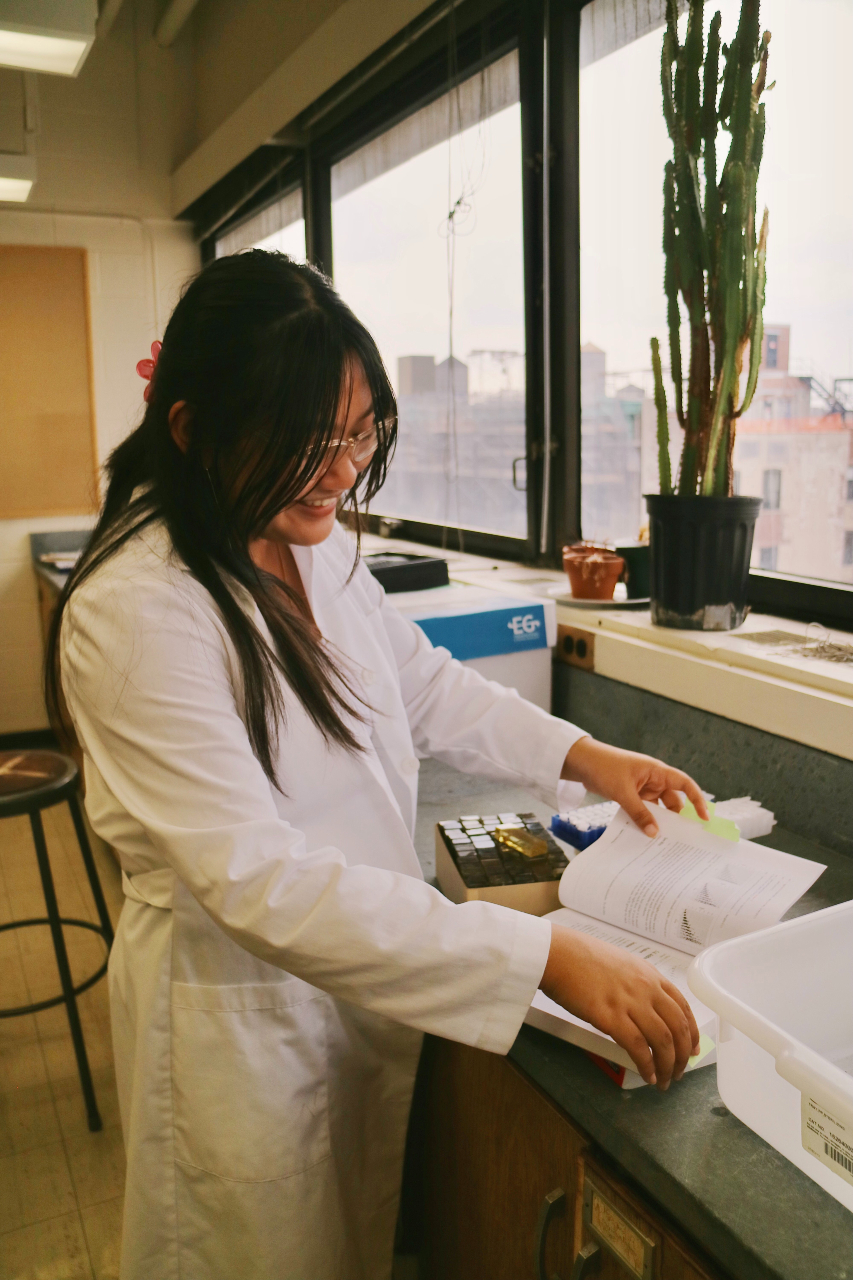

The nature of our research fell under the category of digital botany. The project focused on people behind plant nomenclature also known as 'authorities' (the people who are credited for “discovering” a plant). I used an open source coding program called R to analyze and organize large data sets that included 16,000+ plants from 32 different university greenhouse collections. The goal was to identify trends from the data and visualize the demographic of the authorities.

Who are the top 20 authorities? Who were these people (e.g. their nationality, their relationship to other notable botanists, other occupations they held)? How frequently did they appear across these educational greenhouses? How did Barnard’s Arthur Ross Greenhouse compare to the others in authority makeup?

What are some important implications and contributions of your work?

According to Kew, only three percent of current published discoveries are being made by woman botanists. It’s important to acknowledge implications such as this gender gap, because authorities can shape how we as students perceive and engage with science. Our research highlights western science’s legacies of dispossession, colonialism and imperialism, which brings to question the accessibility of scientific discovery as well as who is not being credited.

What is working in the Callahan Lab like? How have you dealt with any setbacks or challenges while conducting scientific research and how you balance research and life outside of the lab?

It was really insightful working with Professor Callahan. I came in with very little coding experience, so I had to learn on the go and very quickly. It was tricky trying to find the right code workflow or coding argument that my program could understand. Learning to write in R meant that I had to get creative and approach a whole new line of thinking.

Balance in allowing myself to work on the code up until a certain point each day was crucial to the quality and experience of doing research. Maintaining the separation between the dedicated time for research and being off the clock allowed me to come back the next day with a clear mind, ready to tackle the next task.

Lastly, what advice would you give to an introductory biology student interested in research, but unsure of where to start? How did you approach Professor Callahan to join her lab?

Ask around! Your professors are likely doing really cool research. Identify your interests, check out the faculty bios, and send out an email. I was sharing a presentation on a scientific article that used plant models to my Biology Journal Club class when my professor suggested I look into Professor Callahan’s lab.

Can students contact you if they have questions?

If you have any other questions or would like to know more about my experience with SRI research at Barnard, feel free to shoot me an email at tbv2105@barnard.edu!